For a Lack of Words – Text-inspired images in “Sense of a Sack”

I

have a very early memory — perhaps I was seven or eight — of me sitting

on the kitchen counter while my mother spoke to me. Toward the end of

each of her sentences, I would try to guess what she was going to say

next in order to say it before she could. While this might seem

smart-alecky, my intention was to save her some of her allocated words.

You see, I had gotten it into my head that there was a cap on the number

of words we get to use in our lifetimes, and since I was much younger

than her, I could spare a few of mine.

The

idea of a finite and set number of words suggests that words have a

concrete quality. One could easily imagine words being dispensed from a

jar, and from this see a future for me that would include an interest in

two-dimensional and three-dimensional artistic expression. Indeed, I

could very well invert the transition and make a similar case for making

mudpies as a child, and being disappointed that I was not rhetorically

skilled enough to convince anyone to taste them. But the more factual

story is that I started writing poetry and stories in high school, a

practice that continued through college and beyond. Yet, by the time I

was out of college I had moved into performance art as well, and because

of the spatial quality of the stage, sculpture and other media were not

far behind. And now, words, images and objects are all art forms I use.

Still,

there have been plenty of times when one of these art forms,

specifically words, has either failed me or been pushed aside at the

insistence of, or reliance on, other media. However, over time, and

particularly in the last three years, all of the art forms I use have

begun to share the same space. In truth, it remains a struggle, not

because I have not found ways to incorporate all of them, but the level

of self-disclosure and honesty the words seem to insist on leave me with

a sense of completion that I find uncomfortable. The apparent success

turns into a kind of destructive force that annihilates the mystery and

my motivation that would otherwise encourage me to continue along these

same lines of inquiry. I don’t fully understand it, yet it seems to be a

kind of neurosis for it is such an uncomfortable, dissatisfying state

that I have no choice but to distance myself and retreat into the

relative safety of nonverbal abstraction. Eventually, however, something

begins to suggest something else, a resolve rears its ugly head again

and the process of negation begins afresh. I have given this overall

practice, this serially compulsive dialectic, the title, “For a Lack of

Words,” and examples are represented here in this exhibit, “The Sense of

a Sack.”

At

this point in time, “For a Lack of Words” has manifested as three

bodies of work. The first is called “Gist” and is primarily text-based.

“A Persistent Hum” is the sole example of this work in the installation.

The “Gist” series itself arose out of a long-standing observation of

the forms words take on a page, either like a poem’s structure (whether

as a sonnet or free verse) or, in the case of prose, as a somewhat

arbitrary effect of the typesetting. I am keenly aware of and sometimes

distracted by the word spacing when I read. When these unintentionally

framed blocks of text are isolated from the manuscript — if they make

any sense at all — create a new body of text that sometimes paraphrases

the original but more often than not create new, albeit tangential

ideas. The words are conditionally liberated. I say “conditionally”

because they are already placed in a new jar... or even a sack.

In

that most of my reading is art or philosophy-related, the pieces often

reference these subjects, which I find appropriately and pleasingly

meta. Every “Gist” is then presented as a photograph in order to

document the find. I have captured over one hundred of these pieces over

the last three years, but as a corollary to the neurosis I described

earlier, the success of this work has made me to put them aside until a

time comes that I can either literally or figuratively push them outside

of their boxes.

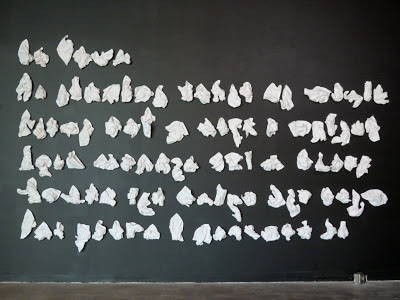

Once

again, I move away from words, which makes for a transition to the two

sculptures, “Love Poem” and “Maquette for the Title of a Poem Intended

to Be Read Aloud.” I have taken the idea of words on a page, removed the

words and replaced them with shapes that mimic the placement of letters

and words. Many of the individual shapes in “Love Poem” are suggestive,

not only of letters but also of discrete objects and not-so-discrete

activities. “Maquette,” however, is a little more oblique: The notebook

is where poems are written, and the gum is chewed, thereby suggesting

the mouth, and when arranged like text, becomes a stand-in for the

spoken word, hence a poem read aloud.

The

hand plays a role in these sculpture as much as it does in drawing or,

for the sake of another transition in this talk, penmanship. The third

body of work in “For a Lack of Words” echoes calligraphy, but as

drawings they are more like cryptograms.Initially inspired by Asian

scripts and the artists Robert Motherwell and Cy Twombly, this may be my

longest-running series of work, numbering in the hundreds, perhaps

thousands, over twenty years or more. I make these drawings as an

exercise in formal considerations. The decisions are quickly made,

almost reflexive, like speaking in tongues with a pen or brush. The

linear aspects balance the expressive and visually lyrical qualities. It

is through the repetition and consistency of their structure that the

drawings suggest content, whether it be words, or in the case in

“Studies I – IV,” a transition from letters and words to landscapes and

then back again. And here’s a clue: think of the color aspects as using a

HiLiter in your textbooks.

But

one might ask what this has to do with a sack, or for that matter, as I

have indicated in my press statement, inspiration from Jacques Lacan? I

have little desire to speak at length about Lacan and his approach to

psychoanalysis, or if you prefer in this case, psycholinguistics, for at

this particular moment I favor the primacy of the artist over the

necessarily anachronistic methodologies of critical examination. Nor do I

think much good comes from cramming the latter into a shape that

attempts to fulfill the needs of the former.

I will, however, allow Lacan’s passage from which I derived the title of this exhibit. Early in his 23rd

Seminar he writes, (quote) “The astonishing thing is that form gives

nothing but the sack, or if you like the bubble. It is something which

inflates, and whose effects I have already described in discussing the

obsessional, who is more keen on it than most.” (end quote) Never mind

that the obsessional has been given personhood in this passage — not so

curious a notion once Lacan mentions that the sack is also a skin, nor

strange to the self-aware artist, suitably petulant in his or her

fascination with both the sack and what should fulfill its purpose.

Instead, I keyed on the word “form,” that it “gives nothing but” and how

this double negative gives an artist both something to push against and

to draw near, to discover anew through serialization and put at risk in

favor of an unknown. The sack, thusly passive, still remains that in

which things are placed. It has meaning only in regard to a function,

and that is to be filled — whether we fill the sack or are the sack that

it to be filled. Likewise, as it seems to me in the widest sense

possible — and I think Lacan would agree with me on this point — it is

the artist’s mania to both fuck and be fucked.

It

is here that we can return to the work presented in the exhibition, for

if you have not already gathered, there are formal aspects that connect

the individual works, primarily in the choice of marks made or in the

case of a couple of the photographs, observed. We may also refer to

these marks as content, which is well and good as I had no grand

intentions beyond the obvious in this regard. Other connections are more

discreet, which I would hope provides some depth to the individual

viewing experience. After all, how can the artist be responsible for or

anticipate the experiences, knowledge and other realities a viewer

brings to the work? Indeed, my own experience of the work has shifted in

that one piece, the book that is listed on the price sheet but is

missing from the exhibit proper, has taken on an unanticipated meaning

for me, it’s creator. It is my understanding that few, if any have asked

to see it unless I am here to force it upon them, epitomizing, if you

will, a certain sense of loss that persists throughout the exhibit.

That

melancholy now extends to the fact that my exhibit is about to be

dismantled. I would therefore hope that after my talk this audience

becomes viewers one last time around. So, in closing yet in an effort to

prolong my experience at Place, while at the same time knowing that I

can beg your indulgence within reason, I shall offer some final,

hopefully clarifying remarks about how specific pieces are intended to

work with others, all to create the theme of this exhibit. And I shall

do so recognizing the risk I take of belaboring the obvious.

I

will start with the Studies I – IV. To my mind, if we take each of

these little paintings on their own terms, they are rather

unremarkable.Nothing special at all. I have confessed to those closest

to me, and now to you, that I think they are rather ugly little

paintings. Yet, overall, I am rather pleased with what they have become.

As a group I find them beautiful. They reinforce each other in their

framing and from frame to frame, developing a syntax or telling a story,

if you will, moving away from abstraction into something we can speak

to as an aspect of nature or a landscape. The colors highlight points of

particular interest while bringing an additional meaning to the title

of the pieces in their arrangements: It is how many of us study, that is

searching out and demarcating key passages in texts. Yet, it may matter

little to the audience that I prefer to bracket such passages and here

have used the colors to mark where I thought each individual piece

failed.

The

video, “The Written Wood,” continues along the same lines. The video

suggests an indeterminate text. Yet, it is not an easy piece to watch,

or to listen to. The distress is intentional. Even an elucidation does

not come easy; the visceral is not readily salved. This also aligns with

an idea I have regarding the practice of asemic writing. (Asemic

writing is a type of drawing that is somewhat loosely aligned to visual

poetry. It is called “asemic” because it is said to have no specific

semantic content. Many of the pieces in this show can be considered

Asemic.) Words sometime elude us, not because of a limited vocabulary

but more that we are not ready for, or capable of an understanding,

whether it be within us or coming from an external source. Instead of a

finite number of words at our disposal, there may be none. In such

cases, the scribble, is a stand-in for the desire to express regardless.

Jumping

over to the photo “I Ching,” I would simply point out that despite a

lack of understanding, we nevertheless make some attempt to gain insight

through some formal process. With the I Ching, the search for

revelation is both internal and external, yet intentionality is still

riddled with the arbitrary. If this doesn’t echo intersubjectivity, I

don’t know what does.

And

then quickly to “Coralish 5,” even when we find an appropriate symbol,

its endurance is not guaranteed. What once may have been made in the

shape of a turtle has been transformed by either thoughtless vandalism

or mindless yet purposeful tectonics. Language is in flux.

Words,

after all, are mere stand-ins, and whether they are used to describe or

defend, comfort or cajole, elucidate or seduce, they offer a security

that is deceptive.Yet, in order not to leave on a sour note, I will

amend that last sentiment by adding that this deception is one we

necessarily must allow ourselves, like an unconscious sin of omission

that is the fragility of communication. There is always something

missing, yet this in no way means that these attempts toward meaning are

not creative endeavors.

No comments:

Post a Comment